JTA – Years ago, when I worked at Forward, I did a cameo in a real-life Yiddish play.

A cub reporter named Max Gross was sitting right outside my office, where he answered the phone. Ina Grade, the widow of Yiddish writer Chaim Grade and a fierce guardian of his literary legacy, was a frequent caller. Mrs. Grade would badger poor Max into dozens of phone calls, especially when a forward story referred kindly to Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer. Grade’s widow described Singer as a “blasphemous buffoon” whose fame and reputation, she was convinced, had come at the expense of her husband.

As Max recounts in his 2008 memoir, “From Shlub to Stud,” Mrs. Grade “became a running joke around the paper.” And yet in Yiddish literary circles, her protection of one of the most important Yiddish writers of the 20th century was serious business: because Inna Grad kept such a tight hold on her late husband’s papers—Chaim Grad (pronounced “beans-deh”) died in 1982 – failing a generation of scholars to get the right measure of him.

Inna Grade died in 2010, leaving no signed will or survivor, and the contents of her dilapidated Bronx apartment became the property of the borough’s public administrator. In 2013, Chaim Grad’s personal papers, 20,000-volume library, literary manuscripts, and publication rights were awarded to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and National Library of Israel, They are now stored at the YIVO headquarters on W. 16th Street in Manhattan.

Last week YIVO and NLI announced the completion of the digitization of “The Papers of Chaim Grad and Inna Hecker Grad”. Making the entire collection publicly accessible online, When the folks at YIVO invited me to come and see the Grade collection, I knew I had to invite Max, not only because of his connection to Inna Grade, but because he is a critically acclaimed novelist in his own right. has become: his 2020 novel “The Lost Shettle”, which imagines a Jewish village in Poland that somehow survived the HolocaustIn many ways a tribute to the Yiddish literary tradition.

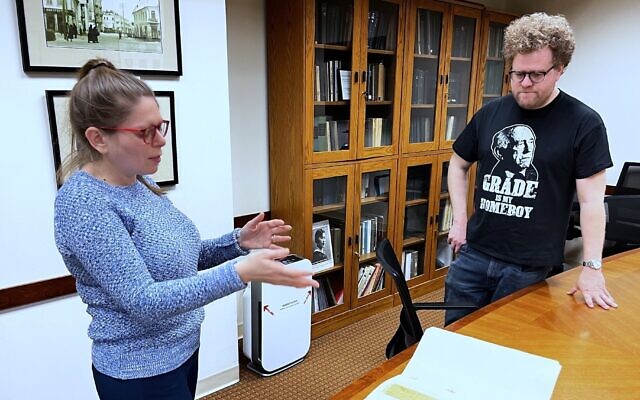

Prior to the release we met YIVO staff who were gobbling up T-shirts worn by Max that featured Chaim Grade’s picture and the phrase “Grade is my homeboy.” (Max said his wife bought it for him, although no one could have imagined a market for such a shirt.)

Grade papers – manuscripts, photographs, correspondence, lectures, speeches, essays – are stored in folders in gray boxes whose neatness defies the years of effort that went into keeping them in order. Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director and CEO, described for us the Grads’ apartment, which he visited shortly after Inna’s death.

Stephanie Halpern (left), director of the YIVO archives, and novelist Max Gross discuss a thick file containing news clippings related to the late Yiddish novelist Chaim Grade at YIVO’s Manhattan offices on February 2, 2023. (New York Jewish Week via JTA)

“It was like a combination of my grandmother’s apartment and a writer’s house,” he said. “Everything was books, books up to the ceiling. You open a drawer in the kitchen where you think there will be knives and forks, there are books, there are manuscripts. You open the cupboard in the bathroom, there are more manuscripts and books and books…. But what I remember most is that there was so much dust on top of a shelf. He placed his fingers about two inches apart.

Inna Grade was Chaim Grade’s second wife. The author was born in 1910 in Vilna (now Vilnius, in Lithuania). He was able to escape to the East during the Nazi occupation, leaving his mother and his first wife behind under the assumption that the Germans would only target adult males. It was a tragic miscarriage, and her death would haunt Grade for the rest of his life. Inna Hecker was born in Ukraine in 1925, and met Grad in Moscow during the war. Married in 1945, they immigrated to the United States in 1948.

Chaim Grade had already established a reputation as a poet, dramatist and prose writer before the war; The English translation of his novels “The Agunah” and “The Yeshiva” and the serial publication of his novels in the Yiddish press brought him recognition in America, for which Yiddish scholar Ruth Wiese calls his “Dostoyevsky genius to animate fiction destroyed Talmudic Civilization” Europe. Jeremy Duber, a professor at Columbia University, says in a release from YIVO that Grade “was imbued with the spirit of the yeshiva world he had left behind; then in possession of the souls and memories of those killed by the Nazis.”

Stephanie Halpern, director of the YIVO archives, showed us physical evidence of that possession: Grade’s notebook, in which he wrote down thoughts and inspirations in careful Yiddish script; Manuscripts of at least two unpublished dramatic works, “The Dead Can’t Rise Up” and “Herban” (“Destruction”); a photo of Grad standing among the ruins of Vilna during his only visit after the war; Photos of the Bronx apartment taken when the couple were still alive, filled with books but still neat.

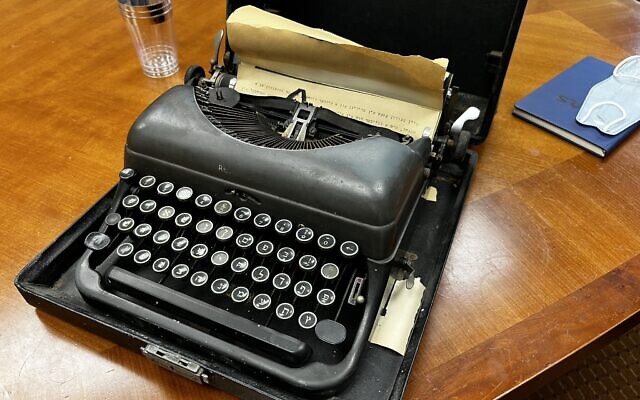

Halpern also showed us the Yiddish typewriter recovered from the apartment, which is believed to be the last page he still worked on.

The archivist is also careful to give Inna her due. After arriving in America she studied literature and earned a master’s degree from Columbia, and often translated her husband’s work. Thanks to him, hundreds of clippings of Grad’s work and articles about him have been preserved.

Chaim Grad’s typewriter, preserved in the condition it was in when the Yiddish writer died in 1982, apparently contains the last lines he ever wrote. (New York Jewish Week via JTA)

Their correspondence shows the lengths she went to protect her husband’s legacy during and after his lifetime, including a bizarre and lengthy letter to the Vatican complaining about Singer. Brent said, “She was the kind of brilliant and creative person only a widow could be.” “And probably devoted to a crazy extent.”

If this all sounds like some Jewish fiction, it is: In 1969, Cynthia Ozick wrote a novel called “envy; or, Yiddish in America“So picky about Yiddish writers consumed with envy for a writer like a grade one singer. Ozik wrote, “They hated him for the wonderful thing that had happened to him—his fame—but This he never mentioned.” “Instead they discussed his style: his Yiddish was impure, his sentences lacked grace and elucidation, his paragraph transitions were amateurish, lowbrow.”

Halpern shows us a mailgram from Inna to the forwards that makes it clear that she and her husband read the story and hated it. In it she describes Ozick as “no less grotesque than evil”.

Brent said of the Archive, for all the Gothic Yiddish aspects of its recovery, “it is probably the most important literary acquisition in YIVO’s post-war history.” He described publishing projects already underway with Shockken Books and other publishers that would draw on the material.

Max and I discussed how it felt to see what had become “a bit of a joke” around the Forward Office placed at the center of an epic exercise in literary patronage. Max is shocked by the way Inna’s personality comes up in the newspapers. “It was she,” he said. “Her passion, her struggle, all these things. It was definitely remarkable to watch.

I remember recalling her interactions with Inna, and how her behavior could seem odd and disturbing, but also admirable and more than a little sad — in that her devotion to her husband’s reputation has also earned scholars the work she wanted to do. would have prevented them from doing what would have made them better known.

“Exactly, but that’s one of the reasons why you get into Yiddish literature, because all these things are true at the same time,” Max said. “Scores like this, rivalries, fights within Yiddish literature are what’s great about it. It’s nice to see that someone actually cared and that literature was taken so seriously. And the pettiness was something you could see in the rest of the world.” Couldn’t separate from.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.