JTA — Starting Monday, many Jews around the world will celebrate Purim in the same way: by reading the story of the heroic Queen Esther, dressing up in festive garb and drinking wine.

For the 900 or so Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina, this will be the first of two annual Purim celebrations.

Since 1820, locals have also observed Purim de Sarai (Sarai is the root of the word Sarajevo) at the beginning of the Hebrew calendar month of Chesvan, which usually falls in October or November of the Gregorian calendar.

That year, the story goes, a local dervish was murdered, prompting the corrupt Ottoman Pasha of Sarajevo, a high-ranking official, to kidnap 11 prominent Jews, including the community’s chief rabbi, Moshe Danon. A Kabbalist named The Pasha accused them of murdering the dervish—who had converted from Judaism to Islam—and held them for ransom, demanding 50,000 groschen silver from the Jewish community.

But the Pasha, a transplant from elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire, deeply resented Sarajevo’s multiethnic population, who considered the Jewish community – then about a fifth of the city’s entire population – an essential part of their home. So the local Jews, Muslims and Christians rebelled together, stormed the Pasha’s palace and freed the imprisoned community leaders.

Since then, Bosnian Jews have celebrated the story by visiting the grave of Zeki Efendi, the Sarajevo Jewish historian who was the first to document it. Dozens of people take part in a pilgrimage every summer to the grave of Rabbi Danon, who is buried not far from the Croatian border in the south of Bosnia, where he died on his way to what was then Ottoman-controlled Palestine.

Over the centuries, many other Jewish communities around the world observed their own versions of Purim based on stories of local resistance to anti-Semitism inspired by Esther and her uncle Mordecai. original holiday story Saved all the Jews of Persia from execution in the 5th century BC.

Here are the stories behind some of those traditions.

Ancona, Italy

Jews settled in and around Ancona on Italy’s Adriatic coast in the 10th century, and by the 13th century, they had established a thriving community, including such figures as the Jewish traveler Jacob of Ancona—who Marco Polo may have been defeated by China – and the famous poet Emmanuel the Roman, who, despite his title, was born in a town south of Ancona.

Although the city’s Jewish community was largely spared by the Holocaust, it has gradually dwindled over the years and is believed to have fewer than 100 members today. However, it’s not short on local Purim stories—the city is known for many celebrations that were established over the centuries.

The first was established in the late 17th century on the 21st day of the Hebrew month of Tevet (usually in January) and marks an earthquake that nearly destroyed the city.

“On the evening of 21 Teveth, Friday, 5451 (1690), at 8 and a quarter, there was a mighty earthquake. The doors of the temple were immediately opened and within moments it was filled with men, women and children, still half-naked and barefoot, who came to pray to the Eternal before the Holy Ark. Then a true miracle happened in the temple: there was only one light, which kept burning until it was possible to provide it,” wrote the Venetian rabbi Yosef Fiammetta in 1741 in his text “or boker,” meaning Is” morning light.

Other Ancona Purims were instituted half and three-quarters of a century later, respectively. The story of the first commemoration nearly destroyed the local synagogue, but miraculously did not, and the next tells of a pogrom that nearly destroyed the community as Napoleon marched through Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. Was.

Today, these stories have largely faded from memory. But a few centuries earlier, Italy had a high concentration of communities that celebrated local Purims – including Casale Monferrato, Ferrara, Florence, Livorno, Padua, Senigallia, Trieste, Urbino, Verona and Turin – some in the 20th century.

The late Italian rabbi Yehuda Nello Pavoncello once wrote, “It is to be hoped that local Purims are not forgotten or restored in communities that have not been completely abolished.” According to the Turin Jewish community“So that the memory of events links us to the infinite links in the chain of generations that have gone before us, who have suffered.”

North Africa

Additionally, the Purim phenomenon was not limited to Europe.

In Tripoli, Libya, local Jews established the so-called Purim Barghul in the late 18th century after the deposition of a local tyrant. Ali Burghul, an Ottoman official installed after the fall of the Karamanli dynasty, brutally ruled the region for two years, treating minorities particularly harshly. After the reconciliation of the clans of Qaramanlis, Burghul was ejected. Jews celebrated on that day, the 29th of Tevet (usually in January).

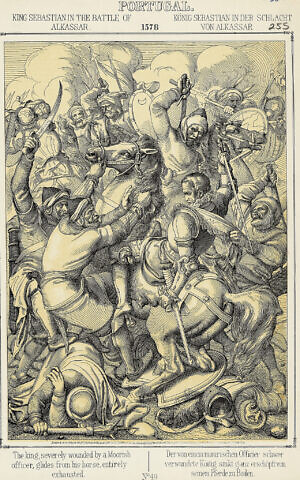

One illustration shows King Sebastian of Portugal as being badly wounded in a battle in Morocco in 1578. (Bateman/Getty Images via JTA)

(Centuries later, in 1970, dictator Muammar Gaddafi established his own holiday, the Day of Retribution, which celebrated the expulsion of Italian officials from Libya; some say it commemorates the exodus of Jews since the formation of the state of Israel.) A few years after Gaddafi’s decree, Libya’s Jewish community had dwindled to less than two dozen, effectively ending nearly 3,000 years of Jewish history.)

In northern Morocco, Jews commemorate the defeat of a Portuguese king, Don Sebastian, who attempted to capture parts of the country but was defeated in a battle in August 1578. The Jews believed that he would prevail if he tried to convert them to Christianity.

There are only about 2,000 Jews left in Morocco today, but some Moroccan communities mark the day into the 21st century.

Zaragoza

Scholars still debate which city was the origin of the Purim of the Saragossa story – it could have been Zaragoza in Spain or Syracuse in southern Sicily, which was often referred to as Siragusa in the medieval era. Both cities were part of the Spanish Empire in 1492 and were depopulated of Jews after the Inquisition.

Either way, Sephardic descendants in places around the world, including Israel and the Turkish city of Izmir, observe their Purim story by feasting on the 16th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat — usually in February — and on the 17th.

A view of the 11th-century palace in Zaragoza, Spain. The Purim of Saragossa story is set in either Zaragoza or Syracuse, Italy. (Getty Images via Houlton Archive/JTA)

The story tells of an apostate named Marcus who defames the Jewish community before a Gentile king, thereby jeopardizing their position. But at the last minute, Marcus’s deception is discovered, and he is killed while the community is being saved.

The story could have been completely fabricated. According to Jewish historian Elliot Horowitz, the setting of this second Purim story may have been a way for the descendants of Saragson Jews, whether Spanish or Sicilian in origin, to maintain a distinct identity in the larger Sephardic diaspora.

“Jewish communities in the Eastern Mediterranean in the early modern period were often composed of emigrant subgroups, each with customs and rituals distinct from their place of origin,” he wrote in his 2006 book “Reckless Rites: Purim and the Was. The legacy of Jewish violence. The “Purim of Saragossa”, the earliest manuscript evidence for which dates only from the mid-eighteenth century, may well have been ‘invented’ by the former ‘Saragosans’, who sought to maintain their distinct identity in the multicultural Sephardi diaspora of the eastern Mediterranean. Looking forward to.”

Regardless of its origin, the Megillah of the Saragossa text continued to be published until at least the late 19th century. It was famous enough that an American Reform rabbi from New York would publish stage play Based on this in the 1940s.