The northern town of Hirsch canceled a screening of a Holocaust documentary that was to be held on Thursday night in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day because the film’s subject, Alfred Hirsch, a German Jew who saved children at Auschwitz , was openly gay.

Other residents banded together to stage their own showing of the acclaimed documentary after it became known that it had been canceled due to objections from ultra-Orthodox community leaders in the city.

The film’s director, Ruby Gat, said the municipality had approached her months earlier to organize a screening of her 2017 documentary, “Dear Freddy”. They set a venue and date – Thursday, 26 January, the evening before the start of International Holocaust Remembrance Day – and GATT also approved promotional materials for the event.

Suddenly, 10 days before the event, the head of Harish’s youth services called Gat and told him that he would have to cancel the event.

During the call, which Gatt recorded, he told her that it was because of “disquiet” within the municipality, that there had been an “explosion” between various officials at City Hall.

He explained that the cancellation of his screening due to opposition from Haredi leaders was part of a wider cancellation of LGBTQ-focused events in the city.

“There is a crisis about [LGBTQ] program in general because we are a mixed city and this is a new program and a new city,” she told GATT, referring to the secular and religious communities that share the city.

He asked her bluntly if it was because of “LGBT-phobia” and she confirmed it.

“At first I was shocked. The next day, I was just depressed. But the day after that I told myself, ‘This is not fair. If I keep quiet about this, things like this will keep happening.’ They told me clearly that it was because it was ‘LGBT’ that they had to do some rethinking, but maybe in a few more years they can do a screening,” Gat told The Times of Israel on Thursday night.

After deciding that the cancellation of the screening was unacceptable, Gatt brought the matter to the public light, speaking to Channel 13, Channel 12 and Haaretz newspaper.

When Nitzon Avivi, a Harish resident, heard about the cancellation, he decided to organize a private screening of the documentary. Avivi, a musician and community organizer, had access to a projector and sound system and found a friend who had a place where they could hold events. He reached out to Gat, who said he’d be thrilled to participate, and then managed to get the word out to various WhatsApp groups and on Facebook.

Finally, more than 60 people gathered at a local dance studio, Sheeradance, to watch the film, which Gat had introduced.

“I have no doubt that this will be the most heartwarming screening I’ve ever been to,” Gat told the audience Thursday night.

‘Dear Freddy’ director Ruby Gait talks to the crowd at a screening of her film in the northern city of Harish on January 27, 2023. (Judah Ari Gross/The Times of Israel)

The municipality has since tried to claim that the cancellation was not due to the film’s LGBTQ content, but because “there wasn’t demand” for the screening. However, this was bolstered by the fact that the event was canceled before the city even publicized it, making it unclear how it could have known in advance that people would not be interested.

Harish Vice Mayor Idit Antonov, who attended the Thursday night screening and who tried to get the city to go back on its decision to cancel the event, confirmed to GATT that despite the city’s claims, the decision to cancel the screening was indeed This was done because of opposition to the film’s LGBTQ content and ultra-conservative components of the city.

Antonov said, “It’s a wonderful film, and I’m glad that at least it was finally shown in Harish.”

Harish, a relatively newly built city, was initially planned to serve primarily Israel’s ultra-Orthodox population. Following a High Court case, the city was forced to open itself to Israelis of all stripes, although significant tensions between its secular and religious residents still remain, and occasionally bubble to the surface, Like the fight on “Dear Freddy”.

In his opening remarks, Gat lamented that his film became the center of such controversy and debate, believing that it sowed division in Israeli society and only detracted from the story of its subject, Freddy Hirsch.

‘Dear Freddy’

The film, “Dear Freddy”, relies on interviews with Holocaust survivors who knew him, animation, archival footage and photography, to recount the eponymous subject’s life and tragic death over the course of 74 minutes.

The documentary begins with Hirsch’s childhood in Germany and his involvement in Zionist and Jewish sports groups, particularly Maccabi. After the Nazis came to power, Hirsch’s family left the country and moved to Bolivia. Freddy moved to Prague in 1935, hoping to eventually emigrate to Palestine.

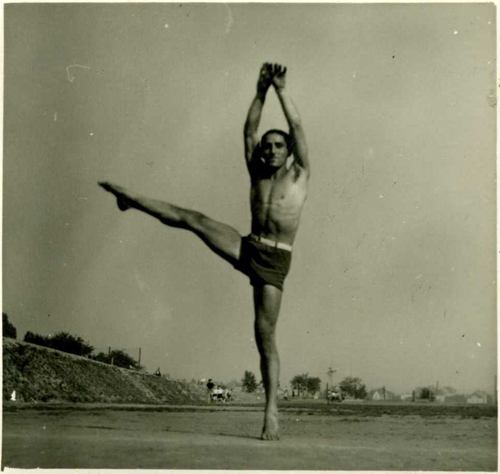

Tall, lean and muscular – and with his hair always carefully coiffed – Hirsch was a firm believer in so-called “muscular Judaism”, a Zionist belief that through building muscle, Jews could rebuild themselves as a new people. will do. Living in what was then Czechoslovakia, he continued to lead Maccabi activities despite the Nazis taking over the country.

Freddy Hirsch, a gay German Jew who saved children in the Holocaust, is seen doing calisthenics in an undated photo. (document for education)

Hirsch’s homosexuality was common knowledge and those who knew him at the time and those interviewed by Gatt for the film said that there were rumors about him and sometimes disparaging comments about how boys Don’t be alone with him. At the same time, this hasn’t stopped him from leading Jewish sports camps or becoming a beloved figure in the community, interviewers said.

In 1941, Hirsch was one of the first groups of Jews to be deported theresienstadt Ghetto. There he became deputy supervisor of children, organizing educational activities and sporting events for them.

Hirsch, a fluent German speaker, was able to persuade the SS to provide better conditions for the children. Although this was not definitively proven, the documentary also indicates that Hirsch had sexual relationships with homosexual German soldiers, giving him greater influence and access to useful information in the ghetto, which he could use to expose the children under his care. Used to help.

In 1943, Hirsch was also able to persuade the Nazis to allow him to organize the Maccabiah Games for children in the ghetto, which were attended by thousands, which boosted morale.

In September of that year, he was deported to Auschwitz along with others from Theresienstadt, although he was given privileged status and put in what were called Terezin Family Camp, where they were allowed to keep their civilian clothes and were not forced to shave their heads, although they were tattooed. (It was later found that a Red Cross delegation should come to inspect the camp in order to keep a healthy population on hand.)

Also at Auschwitz, Hirsch was put in charge of the children, being named supervisor of the children’s block. He accused the infamous, sadistic Nazi Dr. convinced Josef Mengele, who conducted horrific medical experiments on the Jews. He also got a second barrack for the children and improved their conditions. To encourage the children, they painted scenes from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by an artist – Dina Gottliebova – on the walls of the barracks.

Hirsch demanded that the 600 children who were in his care follow strict hygiene and cleanliness standards at the camp, requiring them to wash regularly – even in the cold – and to check for lice. to inspect itself. Survivors credit this with saving many children’s lives as it both helped keep them physically fit and made them appear healthy during the Nazis’ “selection”, in which those who appeared sick or weak would be sent to be killed.

While people regularly died of hunger and disease in other parts of the family camp, the children’s block had an almost zero death rate, which is largely attributed to Hirsch.

However, those efforts were ultimately for naught. After several months in Auschwitz, Hirsch was informed by resistance fighters that in March 1944 the occupants of the family camp were to be “liquidated”—put to death and burned in crematoriums. Seeing his death as inevitable, the resistance movement wanted Hirsch, who was well respected by all the various groups in the camp, to lead the rebellion and set fire to the barracks as a final act of defiance.

Freddy Hirsch, bottom-right, a gay German Jew who saved children in the Holocaust, is seen in an undated photo at a sporting event. (document for education)

What happened next is a matter of intense historical debate and is left open in the documentary. Horrified by the knowledge that all the children in his care were about to be murdered, Hirsch requested tranquilizers to help calm him down. Shortly after taking it, Hirsch lapsed into a coma from an overdose. The next day she was taken unconscious, along with the children she had guarded tightly for months, to be gassed and cremated.

What is unclear is if Hirsch intentionally overdosed or if he was poisoned. Hirsch, along with some other prisoners who had been useful to the Nazis – including Block’s doctor and artist Dina Gottliebova – were to be spared from liquidation. However, if Hirsch had indeed instigated a riot in the camp as the resistance movement wanted, the Nazis would likely have executed them all, even those who were to be spared.

The documentary, based on the testimony of survivors, suggests that the doctors who administered Hirsch a tranquilizer may have deliberately given him an overdose in order to prevent a riot and thus save his life. The other explanation the documentary provides is that Hirsch could not bear the thought of seeing the children he had cared for and decided to take his own life by suicide rather than go to the gas chambers.

Hirsch was 28 when he died.

While other damned champions of children, such as Janusz Korczak, became revered as examples of profound moral courage after the Holocaust, Hirsch’s story remained largely untold for decades until a number of historians began researching him. This is despite the fact that many of the people who were helped or saved by Hirsch in the ghetto and Auschwitz were children or teenagers at the time, meaning that many of them lived decades after the war and could easily trace their activities. could testify about. ,

Historian Dirk Kamper, who published a biography of Hirsch in 2015, believes that Hirsch’s obscurity is due to his open homosexuality, which made him a more challenging figure for people to discuss.

However, Hirsch has become better known in recent years. In 2016, a gymnasium in his hometown of Aachen, Germany was named after him. In 2021, he was honored with a “Google Doodle”, which featured a cartoon of him performing calisthenics.

Gatt said he became aware of Hirsch when he researched an old documentary he had made. Hirsch’s sexuality is certainly discussed in the film – Hirsch’s niece says in it that “the one thing” that her father told her about her uncle was that he was gay, “though that was the most important thing about him.” was the point” – but it is far from the central focus. Gat, who is gay himself, said the documentary is “a story about heroism during the Holocaust,” not specifically about LGBTQ issues.

Far from a fringe or radical film, “Dear Freddy” has been shown regularly by the Kan Public Broadcaster on Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day and has been featured in documentary festivals and events over the years in the US, Taiwan and around the world. Czech Republic.

The film, which is in a combination of Hebrew, English, Czech and German, will be screened next week at Kibbutz Manit, northeast of Netanya. Gat said it would be shown in several cities and towns on Israeli Holocaust Remembrance Day on April 17-18.