Lack of smartphones, data cost, technology literacy, mobile connectivity, increase in screen time, non-academic distraction and many social evils have added to the problem.

where is the money?

Lakshmi Sahu and her husband Purushottam Sahu together earn Rs 5,400 a month in Raipur, Chhattisgarh. Last month he spent Rs 14,000 on a smartphone for his 12-year-old son Kunal.

“We took a loan to buy a phone because we didn’t want our son to miss studies,” says Lakshmi.

The 32-year-old mother works as a domestic help and her husband works as a helper in a general store. The couple has enrolled their child in a private English medium school nearby.

Lakshmi Sahu with her son Kunali

A family already burdened with debt on a smartphone is finding it difficult to recharge monthly data.

“Some days we don’t have money to buy groceries, how are we going to arrange a data pack, I don’t know,” she says.

Most families have only one smartphone that everyone shares.

In Kota, Rajasthan, Shila Bai and her husband Ramavatar have the same smartphone for their six daughters and the girls have access only after the parents are back home from work.

Shila Bai’s 15-year-old daughter Kanchan is a class 10 student. He says that the access to the phone is limited and his father does not let him keep it for long.

“We may have the phone after they get back home, but by then there is either no data or websites take time to load,” she says.

Tech and other issues

Technology literacy is a challenge facing both parents and students across the country as most of them are dependent on basic phones.

According to the 2020 Goldman Sachs report – India Internet: A Closer Look into the Future – only 42% of all mobile phone owners in the country owned a smartphone in FY20. Given the low level of income, the growth rate is expected to slow down.

“My husband drinks a lot and he doesn’t pay attention to Kunal’s studies. I’m not educated enough to teach him. I don’t know how to operate a phone. I get confused,” says Lakshmi.

This is another issue for Jyoti Yadav, who lives in Delhi’s Sarita Vihar.

“I can teach my son Yash who is in class 1, but I take my smartphone to work and have been unable to concentrate on my studies. I have to work to earn a living but I also want to help my child with his studies,” she says.

A single mother who works as a maid and lives in a slum where leaving a child alone is fraught with danger.

“Sometimes I take her with me to work but a lot of people don’t like it. That’s why I tell my neighbors to keep an eye on him.”

Yadav’s smartphone is a second hand set with a broken screen. She is barely able to operate the touchscreen.

net disconnect

Mobile connectivity is another major issue, especially in the hinterland. In some areas, mobile connectivity is barely enough to make calls.

A high speed internet connection is required to access the course material over the internet. Students lose interest due to poor connection and constant buffering of videos.

The Shakti village of Ladakh is home to families of nomads and farmers. Though many private companies have installed mobile towers, villagers are struggling to get proper connectivity on their phones.

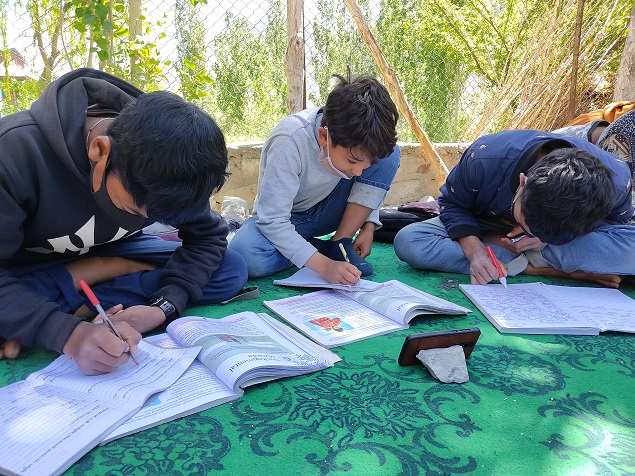

Students share smartphones while attending online classes in Kargil, Ladakh

Sonam Gyatsan, a National Award-winning teacher and headmaster of Government Middle School, Shakti, says, “When the connectivity is disrupted or the data pack runs out, students log out.

In Kerala’s Wayanad, students studying in residential schools in tribal areas have completely lost contact with their teachers after the pandemic.

“Our students belong to the tribal areas of Wayand and live in the forests. They do not have laptops or smartphones and no net connection. We have not been able to contact most of our students. Not only this, they are suffering due to the Covid pandemic. The reason they are suffering is because they have not got food supply,” says K Purushottam, principal Vivekananda Tribal Residential School, Wayanad.

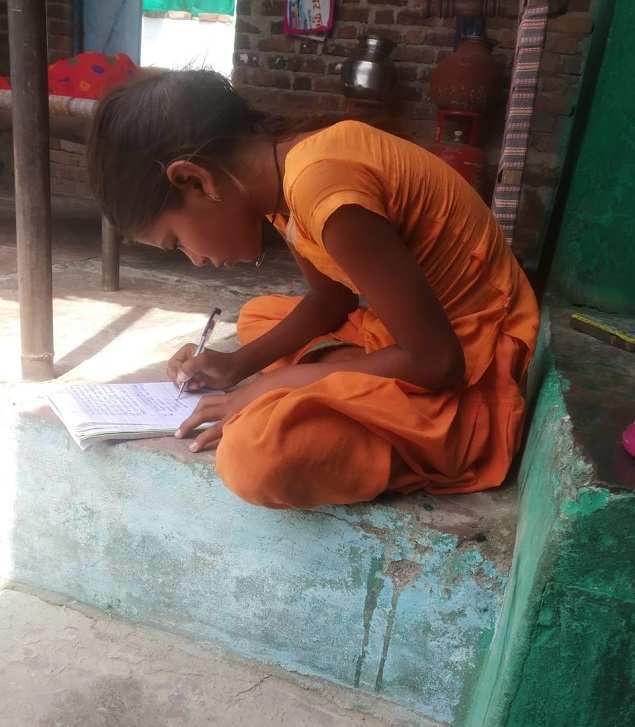

girls, interrupted

In a country where girls are often seen as a “burden” and their education as a privilege, new constraints have added to the challenges.

The lockdown and lack of resources have made studies worse for young girls.

Sheela Bai, who makes a living by selling cosmetic products from door to door in Kota (Rajasthan), is under pressure from her relatives to get her daughters married.

She says, “I don’t want to marry him so soon despite the pressure. I want him to study but how do we do that.”

Her husband says that buying a new phone will lead the girls down the wrong path.

“What’s the need to buy a new phone? What kind of education will they get? It’s the teacher to teach, not the phone!” He says.

While girls are living under pressure to marry, paucity of resources is forcing teenage boys to work as laborers and drop out of schooling.

Fifteen-year-old Mohit, a resident of Karauli district of Rajasthan, studies in a school in Alwar. Neither his school nor his teachers approached him for any help related to his studies.

“The teachers of my school in Alwar said that I can meet them anytime if I face any problem or buy a smartphone if I cannot come. How can I travel for three hours every time I face a problem with my studies? If I had a smartphone, I might not have faced this problem,” says Mohit.

According to Dr Amit Sen, who runs Children’s First Institute of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, the role of children as students, identified by a sense of belonging to the school or a community, has been exhausted and the impact will be severe.

“Now it is even more difficult as children are being asked to get a laptop earlier to attend online classes. I think it is unfair of them or almost disrespectful to ask them to buy gadgets When they can’t even get two meals,” Dr. Sen says.

Mohit now works as a laborer in an onion farm to earn a living.

the long and Winding Road

The pandemic is here to stay and epidemiologists have given very clear indications that a third wave of COVID-19 is inevitable. Although online education is gaining ground, we still have a long way to go.

An Annual Education Report (ASER) survey conducted on 118,838 households in October 2020 states that around 11% of these households have bought a new phone since the start of the lockdown. More than 80% of these new phone purchases were smartphones.

Of those who did not have a smartphone at home, about 13% said their children had access to someone else’s smartphone.

According to Education Director Urmila Choudhary People IndiaAn NGO working in the field of education, the digital divide will disrupt these children badly and governments and NGOs should join hands to solve it.

“When the data runs out, these students don’t join back because they don’t have money to recharge,” she says.

“There are many students who were studying with us, but went back to their villages and it took us a long time to get them back in online classes,” says Choudhary.

lessons of the pandemic

Who is People India working with? South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) Schools to provide education to junior students.

Choudhary says, “Less than 50% students from economically weaker section in Delhi have a smartphone. Earlier our well-wishers used to donate books for children, now we ask them to help us with tablets, phones and data packs. They say.”

His organization also trains parents on how to operate smartphones and tablets.

In Ladakh, teachers are visiting the villages of Changthang, Pangong and Nubra where internet connectivity is very weak. Teachers are connecting with the students of the areas in coordination with the Gram Panchayats.

“We should have community classes for children and send teachers in every village on a roster system so that students can be updated with the syllabus and given homework that can be checked every week.”

“To solve the problem of weak internet, we have set up a mesh network with the help of an NGO. We upload study videos and assignments on the network which children download,” he says.

In Kozhikode, Kerala, parents from the fishing community are sending children to a learning hub run by Nasmina Nasir, founder and director of iLAB, an NGO working for the welfare of coastal communities.

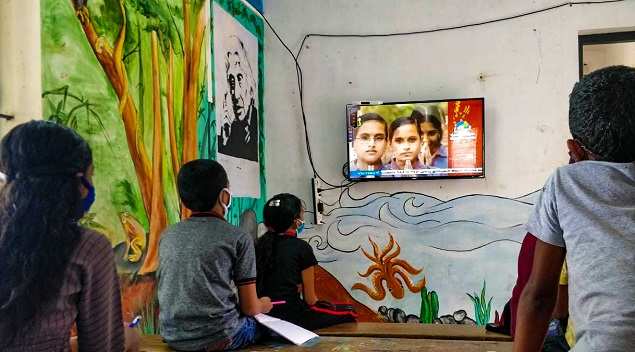

Students in Learning Hub run by ILAB, an NGO

Students in these centers are taught with the help of KITE Victors, a state-run educational channel that provides digital classes to lakhs of students.

“We installed television sets for a group of 7-8 children who are taught with the help of a teacher. It has been successful but has been hampered due to lockdown restrictions and Cyclone Tauta.

Come together

According to Wiplo Shivhare, program head of Pratham, an NGO working towards education among the underprivileged, it is not logically possible for the government to provide smartphones and tablets to every student. The government should develop libraries for the economically weaker students from where they can borrow gadgets and return them later.

“Panchayats and communities should form groups in villages where they can be given tablets with study material without the need for internet,” he says.

“The government can help students study with free data packs. Community servers can be created for students who can download material from these networks,” says Wiplo.

Surely the pandemic has created havoc in our lives. But the brunt of this has been borne by the children and especially the people from the economically weaker sections. Without regular classes, without adequate digital infrastructure, the education of these children has suffered a major setback.

.