LONDON – This is the great whodunit of Zionist lore. On a hot summer evening in June 1933, Haim Arlosoroff was shot by an assassin while he was walking along a Tel Aviv beach with his wife.

At the age of only 34, Arloroff was head of the political department of the Jewish Agency and a rising star in the Zionist movement. Many theories exist, but for the past nine decades the identity of his killer has remained a mystery.

background of murder “The Red Balcony,” A searing tale of murder and high politics, sex and betrayal by novelist Jonathan Wilson. The book hits shelves on February 21.

While some have pointed the finger at Arab nationalists and even Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels for Arloroff’s murder, the cloud of suspicion initially focused on right-wing supporters of Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Only a few days before his assassination, Arloroff had returned from Berlin where he had helped negotiate the controversial Hausra or “transfer” agreement with Hitler’s newly established government.

It allowed German Jews to emigrate to Palestine with some of their property but required that those properties be used to purchase German exports. Jabotinsky, leader of the Revisionist movement, and his followers fiercely opposed the accord, which they viewed as siding with Satan and violating the international boycott of the Nazi regime that Jewish organizations had advocated.

But while right-wingers strongly attacked Arlosoroff – a leading light in Mapai, the forerunner of the Israeli Labor Party – as a traitor, local Arabs saw him as the man responsible for sealing a deal that potentially opened the floodgates of Jewish refugees. Country.

Wilson’s novel loosely tracks the real-life case of two Russian Jews – Avraham Stavsky and Ze’ev Rosenblatt – who were tried for murder in the spring of 1934. Rosenblatt was exonerated, but Stavsky was initially found guilty and sentenced to death. The appellate court eventually overturned the conviction for lack of corroborating evidence. But the legal process did not shake the left’s view of Revisionists as murderers, nor the right’s certainty that it was the victim of a politically motivated blood libel.

But much of the action in “The Red Balcony” surrounds a host of fictional characters: Ivor Castle, a young, Jewish graduate of Oxford University who moves from his upper-middle-class home in London to take a position as an assistant. travel for vicious and cynical defense attorney Phineas Barron; Tsiona Kerem, a mysterious, free-spirited artist whose crucial witness testimony is sent to secure Castle, but with whom the inexperienced lawyer falls in love; Charles Gross, an Oxford contemporary of Cassel and a staunch Zionist; and his American cousin, Baltimore debutante Susannah Green. Through his interconnected stories, Wilson deftly explores questions of identity, law, and politics.

The British-born Jewish author, who lived in Jerusalem in the late 1970s and now lives in Massachusetts, admits to being “fascinated and fascinated” by the short, sad and, often forgotten, story of the interwar British Mandate in Britain Are. in Palestine. “The Red Balcony” is the third time—after the critically acclaimed “A Palestine Affair” and “The Hiding Room”—he has returned to the theme.

“I often find that when people discuss history…they don’t go back far enough to see the early years of Yishuv, the kingdom in waiting, and the struggle that was going on, and what Palestine was like at that time which was actually … a miniature outpost of the British Empire,” Wilson told The Times of Israel.

Mandate Palestine, he continues, was “a fascinating mix of characters and personas and historical figures and competing narratives.” That allure is based, in part, on the fact that “the country was not yet settled.”

“Nothing was fixed and everything was up in the air and up for grabs,” says Wilson. “Different people had different ideas about what the future was going to be and how it was going to work and what the state was going to be.”

But why the Arlosoroff murder?

Wilson states, “Of all the political events, conspiracies, maneuvers and assassinations that took place in that period, the Arloroff assassination is perhaps the most important.”

In fact, he believes that the reverberations of the assassination continue to this day.

“It still plays an important role in Israeli political consciousness,” says the novelist, noting that when corruption charges were first brought against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, one of his aides responded: “Next They will charge him with the murder of Arlosoroff.” Perhaps more fundamentally, Wilson believes that it was an event in Israel’s political history that “cemented the schism between left and right that is still in evidence today.”

history repeating itself

Wilson says that one of the “catalysts” for his decision to write about murder was the 1995 assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. At the time, he recalls, there was much discussion about the exclusivity of the crime—a political motive for a Jew killing another Jew—despite the fact that this may well have been the case in the Arlosoroff case, and the 1957 took place in the murder Israel (Rudolph) Kastner, Which was accused of collaborating with the Nazis.

Wilson notes, “There is one precedent and one division.” “The uproar against Rabin that was unleashed in Zion Square [where an infamous protest took place in which Rabin was depicted in an SS officer’s uniform] The furor was similar to that unleashed against Arlosoroff in 1933. The future is somehow held in the past.

Wilson is aware of the controversies surrounding the transfer agreement and the need to treat the subject with sensitivity to avoid providing “fodder for antisemites”.

“From a novel perspective, it’s a subject so full of ambiguity that it invites the kind of depth that fiction can bring,” he says.

Wilson tries throughout the book to avoid putting the words in the mouths of the actual historical figures who appear in its pages, but he nevertheless allows Arloroff to consider the moral complexity of the transfer agreement. “It was an ugly, tasteless deal,” the Zionist leader in the novel thinks to himself, “but how else could the Jews buy themselves to give up their freedom?”

“I tried to tell the truth about it and try to accurately present the different reactions through my characters,” says Wilson. “One can see why the revisionists were so angry. One can also see why Arlosoroff and his group were trying to save lives.”

Overall, around 50–60,000 German Jews are believed to have escaped an unenviable fate at the hands of the Nazis.

“As a writer of historical fiction, if I’m writing about the aftermath of Haim Arlosoroff’s assassination, I can’t ignore the complexities of the reactions to the relocation agreement,” says Wilson. “I have to present them as they were.”

So who dnit?

Wilson adopts the same parallelism when discussing his thoughts about who might be the culprit behind Arlosoroff’s murder. “I wanted to keep my mind open for the purpose of writing fiction,” he says.

He outlines the many ups and downs in the case that appear throughout the book. For example, Arloroff’s wife, Sima, initially suggested that her husband’s assailants were Arabs, before later claiming that they were Jews. The defense’s argument that Arloroff was murdered during a failed sexual assault on his wife received a boost when a young Arab man provided a detailed confession. But the man, who was in prison for another murder charge, later retracted his claims, saying that he had been bribed by Stavsky and Rosenblatt to confess. And, while it receives only the briefest allusion in the novel, it is also suggested that Goebbels had Arlodorf killed because of rumors that his wife, Magda Goebbels, had a youthful affair with the future Zionist leader, when he lived in Berlin. (Before Arlosoroff moved to Palestine, the pair were close friends, having met as teenagers through Haim’s sister, Liza).

Ultimately, Wilson keeps his thoughts on criminals to himself, preferring instead to quote Chekov’s words: “A writer’s task is not to solve a problem, but to state the problem correctly.” However, he believes that the truth behind the murder is unlikely to ever come out now. Indeed, a commission set up by Menachem Begin to investigate the murders in the 1930s—which the then prime minister hoped would exonerate the revisionists—failed to come to a conclusion about the identity of the real killers. Wilson describes the 90-year-old case as a “frozen aspic”, a view of who was responsible that was unlikely to move.

“It’s not like there’s going to be any new evidence coming out that will conclusively prove it one way or the other,” says Wilson.

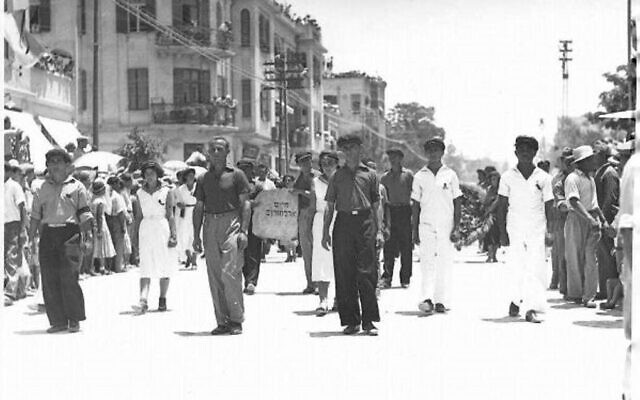

Haim Arlosoroff with Chaim Weizmann (to his left) at a meeting with Arab leaders at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, April 8, 1933. (Weizmann Archives / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

conflicting loyalties

The novel also successfully highlights the conflicting loyalties and identities of Mandate Palestine.

The palace, for example, feels no special connection with Jews in Palestine or the country, is largely indifferent to the cause of Zionism, and does not feel any sense of allegiance to the Yishuv. “He’s on an adventure,” says Wilson, “but while he’s there he begins to question himself and question his identity.”

In contrast, Gross is an ardent Revisionist Zionist and supporter of Jabotinsky, views Castle as frivolous and gullible, and sheds no tears over Arloroff’s murder. The two men, Wilson believes, thus in many respects represent the polarities of the British Jewish response to Zionism and Palestine during the war years.

But Castle’s lack of interest in Palestine or Zionism does not mean he is not aware of his own Jewishness. In Britain, he feels like “an intrusive guest”, says the book.

“There’s no denying the antisemitic undercurrent experienced in England,” says Wilson.

At the same time, however, he recognizes that his home country has hardly hindered his family’s aspirations and success, with their home in London’s wealthy St John’s Wood and Oxford-educated children.

Further complexity and color is added by the Baron – “loyal to none,” in the words of the novel – who, despite being a British Jew, treats Jews, Arabs, and the British themselves with equal dolls of derision.

As Wilson notes, the British administration in Palestine was ideologically heterogeneous, consisting of British Jews who were supporters and opponents of Zionism, as well as non-Jewish British officials who were sympathetic to Jewish aspirations for statehood. Used to keep, while others were. Definitely Arabic in their inclination.

But Wilson also acknowledges that the book’s subject matter and characters are not without personal resonance.

“I am drawn to the period not only because the history is so fascinating but also for personal reasons … these issues are perhaps related to my own struggle about my own British Jewish character,” he explains. “I’m interested in the tug, pull and push of these different issues of identity, which seemed very fluid during that period and continue to be for me when I lived in Israel 40 years ago.”